Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

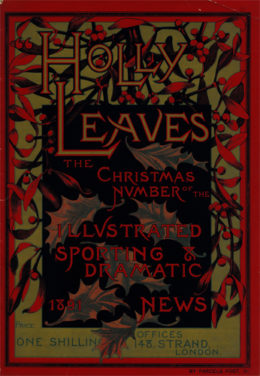

Today we’re looking at Bram Stoker’s “The Judge’s House,” first published in the December 5 1891 issue of Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. Spoilers ahead.

“‘It is,’ said the Doctor slowly, ‘the very rope which the hangman used for all the victims of the Judge’s judicial rancour!’ Here he was interrupted by another scream from Mrs. Witham, and steps had to be taken for her recovery.”

Summary

Malcolm Malcolmson, mathematics student, seeks a quiet place to study for his examination. He chooses Benchurch, a sleepy market town where he has no acquaintances to distract him. Fate’s apparently guided him, for he’s able to lease a long-unoccupied Jacobean manse fortified by a massive brick wall, solitude enough for anyone. His landlady at the town inn, motherly Mrs. Witham, pales when she hears he’s taken the Judge’s House. Its builder was indeed a judge, and a notoriously harsh one. The place has had a bad reputation for a century, though precisely why she doesn’t know. But if Malcolm was her boy, he wouldn’t sleep there one night!

Malcolm thanks her, even as he laughs at her fears. A fellow wrestling with Harmonical Progression, Permutations and Combinations, and Elliptic Functions can have no bandwidth left for less rational mysteries. He finds an old woman to “do” for him and takes for his apartment the house’s great dining room. Mrs. Witham makes his bed cozier with a screen, though the thought of bogies looking over the screen drives her from the house. The charwoman, Mrs. Dempster, is more practical. “Bogies,” she opines, are everything but bogies — rats, mice, beetles, creaky floors, loose roof slates. Why, does Malcolm suppose the dining room wainscoting isn’t full of rats, so many years since anyone’s lived there?

Luckily Malcolm’s no murophobic. As the resident rodents get used to his intrusion, they make a great racket: racing and gnawing and scratching behind the walls, over the ceiling, under the floorboards. Some even venture from their holes, but they strike him as more playful than threatening. Soon he’s deep in study that only a sudden cessation of rat noise disturbs. He looks up to see a huge rat in the very armchair where he took his evening tea, its eyes baleful. He rushes it with a poker and it dashes away up a heavy rope hanging by the fireplace, the pull-cord of the great alarm bell on the roof.

Next morning Mrs. Witham objects to Malcolm calling the huge rat “a wicked looking old devil” — many a true word’s spoken in jest!

The “old devil” reappears that second night, again heralded by silence. Malcolm hurls books at it. Later he notices that no weighty math treatise bothered the rat, only the Bible his mother gave him. He also notices that the great rat disappeared into a hole in a dirty painting. He asks Mrs. Dempster to clean the rat’s retreat so he can see what it depicts.

That day he meets a Dr. Thornhill in Mrs. Witham’s sitting room. The good landlady has summoned the physician to council Malcolm about his bad habits of drinking too much tea and sitting up too late. Malcolm agrees to take better care of himself, and tells of the great rat’s latest antics. Mrs. Witham has hysterics. Thornhill notes that the alarm bell rope, the one the rat climbs, is the very rope the old Judge used to hang his victims.

Malcolm returns to the Judge’s house. Mrs. Dempter’s lit a cheery fire, for a storm’s brewing. The rising wind roars around chimneys and gables, making “unearthly” noises throughout the house. Its force even moves the alarm bell, so that its pull sways unnervingly, “the limber rope falling on the oak floor with a hard and hollow sound.” Malcolm gets a start from the cleaned picture, a portrait of the Judge himself in his scarlet and ermine robes, seated in the great rat’s favorite armchair. His eyes shine with the same malevolence as the great rat’s.

Meanwhile, the great rat has chewed the bell pull through, sending a long coil of rope to the floor. Malcolm chases the creature away. When he turns back to the portrait, he sees a Judge-shaped blotch of unpainted campus. With dread, Malcolm looks at the armchair.

The Judge, flesh and robes, sits in it. While Malcolm stares paralyzed, the man dons a black cap, takes up the rope and fashions a hangman’s noose. Like a cat playing with a mouse, he tosses the noose repeatedly at Malcolm, who barely dodges each throw. The Judge’s baleful eyes hold his, freeze his will.

He wrenches himself free and sees that the other rats are streaming from their holes and leaping to the dangling end of the bell pull, one after the other, until their combined weight begins to sway the bell. Soon they will set it ringing, and draw help!

Anger brings a diabolical scowl to the Judge’s face. No more playing around. Eyes like hot coals, he approaches Malcolm and tightens the noose around his neck. His nearness completes Malcolm’s paralysis, and he doesn’t resist as the Judge carries him to the armchair, stands him on it, steps up beside him and ties the end of the noose to the bell pull. As he touches the rope, the rats flee squeaking; as the Judge descends, he pulls the chair out from beneath Malcolm’s feet.

The ringing alarm bell draws a crowd of Benchurch residents. Dr. Thornhill leads them into the dining room, where Malcolm dangles dead. The Judge is back in his picture, wearing a malignant smile.

What’s Cyclopean: The descriptive adjectives come out in full force for the Judge himself. His face is “strong and merciless, evil, crafty, and vindictive” as well as “cadaverous,” with that vital mainstay of Victorian (and, my housemates point out, modern) villains, “a sensual mouth.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Greenhow’s Charity House is awfully paternalistic towards its denizens, keeping them on a strict curfew. Of course, their harsh rules do keep Mrs. Dempster from getting hung by a ghost-infested rat, so perhaps they have a point.

Mythos Making: Lovecraft was fond of rats, and haunted houses, and math. And houses haunted by Nyarlathotep-granted rat-like familiars who can teach you really esoteric math.

Libronomicon: Mathematical treatises are perfect for throwing at leering rats. Don’t neglect your mother’s Bible, either, especially if the rats in question are haunted.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Malcolm seems perfectly sane, just… not too bright, outside his narrow area of study.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’ve completed my masters thesis. I’ve gone through the intensive final months of my dissertation, and the last-couple-chapters-done-any-day-now sprint of writing a novel, which is surprisingly similar. So I can sympathize with the desire to get away from well-meaning friends and entertaining temptations, somewhere far from cell phone service and wi-fi where you can just focus. I’m entirely with Malcolm2 as he searches the train schedule for the dullest stop, and finds an inn far from any possible company.

Where the inn becomes insufficient, though, we part ways. Malcolm2 has weird ideas about how to avoid procrastination. House abandoned for years, barely in habitable condition? I’ll take it! I can always concentrate when there’s a decade’s worth of cleaning waiting to be done! Dust on everything? Even better, nothing like allergies for the academic mind. Rodents have taken over? I’ll just make servants come every day to this rat-infested pile so I can study in rat-infested peace and quiet. Infested by possessed rats? Perfection itself!

Personally, when I need to concentrate, I like a well-kept house with a great restaurant nearby that delivers. But maybe that’s just me.

Stoker is of course a master of horror, and he definitely has a way with atmosphere. The final confrontation between Malcolm2 and the judge is genuinely chilling. However, Stoker also has no shame about driving a story through pure plot force, plus a protagonist who dives head first into a ball pit full of idiot balls. The biggest Plot Item, of course, is the alarm bell, which spends the whole story shouting, “Look at me! I’m on a mantle! Whee!” before going off in not-exactly-as-expected fashion at the end. The twist works, but I spent the whole story wondering how that particular alarm with that particular rope ended up in that house in the first place. It’s not exactly normal, is it? Having an alarm in your house that can be heard all over town? That’s sort of an official-building thing, not a town-official’s-private-home thing. Also, unless the judge was in the habit of hanging people in his own house (and he may well have been, but you’d think someone would have mentioned such a juicy detail), hangman’s nooses don’t usually require multiple stories worth of rope.

I imagined our cruel, execution-happy judge forced at last into retirement. “Damn it, now I can’t terrorize the town with my unjust verdicts. What can I do to keep the joy in my life? Aha! I’ll have this alarm installed and wake everyone up at random intervals!”

He does seem like the sort who enjoys theatrics. After all, he could have strangled Malcolm2 in his sleep—but no, he wants to glare at him in rat form, then escape his picture frame to play Evil Wonder Woman with the noose.

I’m sure the actual connection between this story and Lovecraft’s work is detailed in our friend Howard’s own writings. But my own mind was inexorably drawn to “Dreams in the Witch House,” so very much like “The Judge’s House” and yet so totally different. I want to think of it as a rejoinder: I’ll show you what kind of haunting is best for mathematical study! Walter Gilman doesn’t ultimately do any better than Malcolm2, but at least he gains real mathematical insight along the way. Plus a bonus trip to the elder thing homeworld! If you’re going to sacrifice yourself on the altar of geometry, you really ought to get something out of the experience that isn’t available at your average bed and breakfast.

Anne’s Commentary

In our usual suspect monograph, Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft praises Abraham “Bram” Stoker for the “starkly horrific conceptions” of his novels but laments that “poor technique sadly impairs their net effect.” The Lair of the White Worm could have been a favorite, what with its gigantic primitive entity lurking in an ancient castle vault, but damn it, Bram, you had to screw up the “magnificent idea by a development almost infantile.” Dracula’s good, though, and “is justly assigned a permanent place in English letters.”

Howard doesn’t mention “The Judge’s House,” but in my opinion, it’s a better haunted-house tale than his paragon of last week, “The House and the Brain.” Instead of cramming all the standard scare tropes into a small space, thus diffusing their impact, it focuses on three: the perpetrator of evil in life whose sheer malevolence survives death; the avatars of that survival, here the giant rat and the portrait that won’t stay put on canvas; and the rationalist overwhelmed by that which his philosophy dreams not of (innocent/amiable subtype.) This focus creates the “net effect” Lovecraft missed in Stoker’s lesser novels—for me, an atmosphere of rising dread that chokes slowly but in the end as surely as the noose that collars Malcolm Malcolmson. Luckily the choking’s not fatal—the reader lives to reread the story whenever she wants a cautionary tale about the dangers of renting without due diligence. Oh, and when she’s in the mood for rats.

Rats! They scurry and gnaw and scratch their way through so many classic works of horror. Lovecraft gave us two great rodent stories in “The Rats in the Walls” and “The Dreams in the Witch House.” Stoker also used them as the Count’s minions in Dracula. M. R. James has one story called “Rats” in which rats don’t even appear—they’re just scapegoats for the real horror, as in “Pickman’s Model.” Of course it’s rats trying to get out of that well, no ghouls around here, nope, no way. And as Mrs. Dempster wisely notes, “Rats is bogies and bogies is rats!”

What is it about rats, anyway? Okay, they raid our food supplies. And, in modern days, chew on our wiring. And reproduce at a ridiculous rate, from a primate’s point of view. And make noises in walls and startling dashes across floors. And have naked, wormlike tails and twitchy whiskers and high-pitched squeaky voices. Then there’s that unfortunate Black Death thing. Speaking of which, I don’t think I’d mind rats much, or their cuter cousins mice and voles, if they didn’t carry so many diseases I could catch! Really scary diseases. The whole time Mrs. Dempster was sweeping up the Judge’s dining room, I was thinking, Nooooo, you’re going to get hantavirus, and so’s Malcolm! Or Lassa fever, or Machupo, or any number of less exotic but still nasty infections! Airborne rat droppings are no joke, woman.

Nor are airborne rats. No, I’m not talking about bats. Horror movie addicts will recall the shivery Willard, in which offscreen animal handlers threw unsuspecting rats at a screaming Ernest Borgnine! Terrifying, right? Then there was the ultimate abomination of Michael Jackson crooning “Ben.”

Not that Ben wasn’t a good rat, when humans didn’t push him too hard. Rats can be endearing. People keep them as pets. You can bring one to Hogwarts as your familiar or star them in Disney and Pixar movies. Which brings me to my first ever reading of “The Judge’s House,” when it confused the moral hell out of me.

I was young enough to believe in absolutes, okay? Those rats all had to be bad, not just the big baleful one. So why did the regular-sized rats always make themselves scarce when Big Baleful came along? Surely they weren’t scared of him? Maybe they were just being respectful of his Evil Magnificence! Yeah. But then why did Malcolm not mind the regulars? Why did he even think of them playful company? And why, oh why, did the rats try to thwart the Judge by ringing the alarm bell? They were on his team, surely.

Now I see they weren’t. In fact, they probably resented the Judge for appearing as a rat and giving them a bad name, like it wasn’t hard enough to scamper in the world as a rat. Besides, the Judge (unlike “House/Brain’s” sorcerer) was AN EBIL BEYOND NATURE, hence intolerable. All natural creatures had better band together against him!

A little space left to express my appreciation for Mrs. Witham as both a touch of comic relief and as representative for the wisdom of superstition and intuition. Mrs. Dempster, Dr. Thornhill and Malcolm himself represent common sense, reason, intellect. Those things saved the “House/Brain” narrator, who might posit that Malcolm fails because he’s a neophyte to the uncanny, unprepared for so powerful a manifestation as the Judge.

Stoker implies that Malcolm’s rationality keeps him from learning a life-saving lesson from his flung Bible. Math tomes don’t bother the Judge—he simply dodges these weighty symbols of reason and science. No, it’s only religion, only faith, that could have preserved the young scholar. Too bad he was no Van Helsing, a doctor of divinity as well as of medicine and law, wielder of crucifix and Host as well as books and physician’s kit, hence the ultimate slayer of Big Bads!

Next week, parenting tips from the Goat With A Thousand Young—join us for Nadia Belkin’s “Red Goat Black Goat.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots (available July 2018). Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

An enjoyable tale, though I was expecting Malcolm to survive right up until he didn’t. Alas, I found myself constantly distracted. Not Stoker’s fault, more the result of reading on line. “Hmm, what exactly is Jacobean architecture?” Open up Wikipedia and find out. “Senior Wrangle? Pratchett didn’t make that up?” Back to Wikipedia (and unlike at Unseen University, the Senior Wrangler isn’t a member of the faculty, he’s the top math student of the year at Cambridge). That made it difficult to really immerse myself in the story.

I liked this well enough, but I thought the ending was a bit of a letdown. The image of the judge very slowly trying to lasso someone was more on the comic than horrifying side for me. I did think that the rats were going to save Malcolm, son of Malcolm or that the doctor would burst in. Sadly the rats were limited and the doctor, I don’t know fell asleep since he refused to drink any of that wicked tea?

I appreciate the details regarding the “morality” of the rats. Spooky animals are great, but as a wildlife biologist, it’s hard for me to suspend my disbelief when animals are portrayed as malevolent.

Also, fun fact: Bram Stoker “stole” his wife from Oscar Wilde, who had been courting her when she and Bram met. Somehow I think Oscar was not to broken up about it.

@2: I felt kind of let down, too. Maybe it’s because I actually really like rodents (I used to have pet mice), rats included, and I wanted the rats to succeed in their life-saving efforts.

I first encountered this story in an early issue of Warren’s Creepy magazine in comic book form faithfully adapted by the great Archie Goodwin with atmospheric illustrations by the wonderful Reed Crandall. The Creepy crew did a lot of Poe, Stoker, and Bierce adaptations, but I don’t recall any Lovecraft.

I like rats. I like many fictional rats, especially Templeton in Charlotte’s Web, who I adored as a kid because reasons, and the Raised Rats in Keys to the Kingdom, who I still love because other reasons. I like some real rats, including my pet Byral, though I never had another pet rat because they have such short lifespans and it’s so sad when they die. But I don’t think I would like to live among the rats in this story.

Red Goat Black Goat...*wriggles with anticipation*

Glad I wasn’t the only one thinking hantavirus!

I was actually leaning forward in my seat reading this, when it was a race between the rats ringing the bell and the judge throwing the noose, as silly as that image is now that I think about it. Well written.

@@@@@ BrianDolan I was also thinking hantavirus during “Rats in the Walls,” but since they were ghost rats, I guess they just shed ghost viruses. Though on the other hand, this idea of ghost viruses begins to intrigue and unnerve me…

@@@@@ AeronaGreenjoy And if your pet rat does live a long time, it must be an animage.

The Water Rat aka Rattie is my favorite fictional rat. I still get choked up in the chapter in WIND IN THE WILLOWS where he’s tempted to roam by the bewitching traveling rat.

Maybe they’re also ghost rats? Ghosts of all the people the judge wronged in life? And that’s why they can make the bell ring so much louder than it should be able to?

Although, I’d expect an army of ghost rats to win out against one, lone ghost rat. On the other hand, maybe they couldn’t believe how inept Malcolm Squared was at ignoring danger signs or taking a few defensive steps.

@9 Anne: I hate to burst your bubble, but Rattie is actually a vole. Specifically a European water vole (Arvicola amphibius). I always thought he was like a wharf rat or something until one of our cats brought one home and I looked it up. Considering we have half as many fruit trees as we’ve actually planted because of the little buggers, I’ve no great love for Rattie anymore.

Just want to add that this story was inspired by J. S. LeFanu’s “Mr. Justice Harbottle”, but with Stoker’s added gruesomeness. It’s been ages since I read it, so don’t remember how close it is.

For more nasty rodents, see Stoker’s “The Burial of the Rats”

@12 I just read “Justice Harbottle” a month or so ago! This story actually reminded me of it, because another story involving a “Hanging Judge,” but I didn’t realize one was inspired by the other. I think in that story the judge’s ghost scares a guy pretty badly, but doesn’t do much else.

Maybe they’re also ghost rats? Ghosts of all the people the judge wronged in life? And that’s why they can make the bell ring so much louder than it should be able to?

That was my take on it, they didn’t scamper because the Judge Rat was supernatural, they scampered because they feared him in undeath as they feared him in life.

I thought Stoker telegraphed the ending rather ham-handedly, that rope was a clear-cut Chekov’s Gun.